The Federal Reserve is the central bank of the United States. Like most central banks, it provides emergency liquidity to alleviate capitalist crises. Like all central banks, it is privately owned. In particular, the Rockefellers and Morgans were instrumental in its creation, and as of 2018 Citibank (Rockefeller) and JP Morgan Chase (Morgan) are the two major shareholders in the New York Fed, together owning more than 70% of shares.[1]

Prehistory and History[edit | edit source]

A Marxist view: Elastic Currency and Crisis Theory[edit | edit source]

[T]he money market can also have its own crises (wholly or mostly unrelated to industrial disturbances) .... In this connection there is still much to be ascertained and investigated especially in the last twenty years. - Engels, Letter to Conrad Schmidt : London, October 27, 1890.

Marx deduced the possibility of a general crisis from the asymmetry latent in the process of capital expansion itself. Namely, the possibility that "the supply of all commodities can be greater than the demand for all commodities, since the demand for the general commodity, money, exchange-value, is greater than the demand for all particular commodities." (Marx-Engels reader, Crisis Theory) In times of crisis, money becomes scarce, ruining those who get caught holding the bag (of commodities). Behind all this is the necessity that value, in order to expand, must transform itself continuously between use and exchange values, and that only in the passage from commodity to money can surplus value emerge. In M-C-M', C-M' is therefore the critical junction, and the problem which emerges time and time again is that C cannot become M' without the ruination of countless capitalists. All of this is in the context of falling profits. "The gradual growth of constant capital in relation to variable capital must necessarily lead to a gradual fall of the general rate of profit." In Capital Volume III Marx outlined several "counteracting influences" by which capitalists could escape this dilemma - if only for a time. My thesis here is that the mitigative role played by central banks is to be understood as such a 'counteracting influence,' one unrecognized by Marx. Whether this takes the form of direct asset purchases and bailouts or an elastic money supply is unimportant - the essential function is to secure the purchase of those commodities which, if the Market remained 'free,' could not have been sold without ruin.

In so far as the payments balance one another, money functions only ideally as money of account, as a measure of value. In so far as actual payments have to be made, money does not serve as a circulating medium, as a mere transient agent in the interchange of products, but as the individual incarnation of social labour, as the independent form of existence of exchange-value, as the universal commodity. This contradiction comes to a head in those phases of industrial and commercial crises which are known as monetary crises. Such a crisis occurs only where the ever-lengthening chain of payments, and an artificial system of settling them, has been fully developed. Whenever there is a general and extensive disturbance of this mechanism, no matter what its cause, money becomes suddenly and immediately transformed, from its merely ideal shape of money of account, into hard cash. Profane commodities can no longer replace it. The use-value of commodities becomes valueless, and their value vanishes in the presence of its own independent form. On the eve of the crisis, the bourgeois, with the self-sufficiency that springs from intoxicating prosperity, declares money to be a vain imagination. Commodities alone are money. But now the cry is everywhere: money alone is a commodity! As the hart pants after fresh water, so pants his soul after money, the only wealth. In a crisis, the antithesis between commodities and their value-form, money, becomes heightened into an absolute contradiction. Hence, in such events, the form under which money appears is of no importance. The money famine continues, whether payments have to be made in gold or in credit money such as bank-notes.[2]

A variable money supply allows liquidity infusions which circumvent the breakdown of payments described above. When there is a crisis, what happens is that no one will part with money to buy commodities which need to circulate, and so the whole cycle breaks down. Under and elastic currency regime, such a crisis will be met with infusions of artificial liquidity. It is a sort of cardiopulmonary recitation of the economic body - blood stops flowing, but an outside pressure can get it going again.

It is only a temporary measure, as it had to be, lest inflation be rampant, something undesirable at that time. The idea was that the 'elastic currency' would be self-liquidating as businesses and banks paid off their loans, returning it to the federal reserve where it would be retired from circulation. This allows capital to deal with crises on a case-by-case basis, but what of the falling rate of profit in general? In theory, the falling rate of profit should continue, and ultimately, however sophisticated the methods of dealing with individual crises become, the situation should become untenable. At some point, as the rate of profit goes on decreasing, the 'elastic' currency can't stretch anymore. But after WWI, the gold standard was effectively smashed, and since 1971, even the formal pretense of 'elasticity' (stretching with respect to gold) has been abandoned. As a distinguished assembly of bourgeois simpletons explained to a fiscally anxious congress during the 90s, failure to expand US debt: "could worsen the economic downturn, causing greater loss of jobs, production, and income."[3] In other words, US debt (the global money supply) must continuously expand - the alternative being prolonged global capitalist crisis.

Before the Federal Reserve: the National Bank System and the New York Clearing House[edit | edit source]

Since 1863 America had operated under the National bank System, a veritable relic. Ostensible decentralization left banks across the country at the mercy of New York. Created by treasury secretary Salmon Chase in the midst of the civil war, banks partaking in the system had to invest in a proportionate amount of government bonds, deposited with the treasury as collateral, in order to issue notes. Chase wanted to force banks to invest in government debt in order to finance the war, and in that desperate context, to that specific end, the system worked well enough. But half a century later it was an unwieldy and inflexible giant. Currency was inelastic since it could only expand via investment in government bonds, bearing no relation to the level of trade. Strict reserve requirements keep 25% of NY deposits locked away, and similar restrictions on other banks kept reserves largely immobile. At the top, there was nothing, as member banks acted in their own interest. In times of crisis, currency remained inelastic, strict requirements kept existing reserves immobile, and there was no central governor, nothing that could coordinate the system toward response.

De jure, the system was acephalic and possessed no recourse to elastic currency. De facto, things are complicated by the presence of the New York Clearing House. Already by 1860 the “largest ten banks in New York City [came to possess] 46% of the total banking assets of the City.” This ongoing concentration of capital was reflected in the explicit organization of New York Banking during the 1850s in the form of the New York Clearing House Association, formed 1853. Originally organized to virtualize specie transfer, the Clearing House “soon developed into a mutual association capable of developing and enforcing cooperative action among the City banks … controlled by a committee composed of five bank officers, usually representing each of the most powerful banks in the City… regulating the admission or expulsion of Clearing House members.”[4]

By 1907, the organization functioned in this vacuum as an unofficial 'bankers bank.' It took care of the daily exchange of checks between banks and, more importantly, they would pool member bank reserves and issue emergency currency ('loan certificates') to mitigate fallout during crises.[5] Holding this power, they could dictate terms to the lesser houses during crises. To deny their services at such a juncture was to destroy, and they knew this. With this power, the clearinghouse, "dominated by the more conservative and solidly entrenched institutions which were either within the Morgan sphere of influence or the National City Bank [Rockefeller] sphere of influence," imposed an order on New York finance which favored establishment finance.[6]

Necessity: the 1907 Crisis[edit | edit source]

Despite the grumblings of certain bankers, the question of currency/banking reform could wait so long as economic conditions allowed it to be ignored. After the 1907 Crisis, bankers as a class could no longer ignore it. As they so often do, the crash followed a period of feverish speculation. By the fall of 1906, this boom was beginning to drain English gold across the Atlantic, and the Bank of England took notice. As Frank Vanderlip reported to James Stillman, “The Bank of England is extremely nervous on the subject of gold exports.”[7] Later that fall, the Bank of England dropped the hammer.

London raised its interest rate from 3.5 percent to 6 percent. The Reichsbank in Berlin raised rates as well. Since international capital ever flows to where the yield is highest, these moves inevitably induced investors to ship their gold back across the Atlantic. The Bank of England further insulated the mother country from the overheated American economy by directing British banks to liquidate the finance bills—short-term loans—that they provided to American firms, thereby tightening credit.[8]

When the Mercantile National Bank, along with a number of failing trusts, appealed to the Clearing House for aid, the Clearing House demanded the "immediate resignation of Messrs. Heinze, Morse, and Thomas from all their banking connections."[9] For days on end the newspapers blared the casualties of the Clearing House sterilization campaign. As the spectacle grew, the public began to balk, and a run began on banks and banking trusts. Already, the American economy was headed toward crisis. More immediately, the crisis was caused by the failure of a bid to corner the copper market by F. Augustus Heinze of the United Copper Company in collaboration with his brother Otto and the notorious Charles W. Morse. Over mid-October an attempt was made to squeeze short sellers, but the attempt failed. Heinze and company were ruined.

the damage done by these failures would probably have been limited had Heinze and his friends not been bankers as well as gamblers. Heinze was president of the Mercantile National Bank; Morse and Thomas were directors of it... depositors naturally became suspicious and began to withdraw their funds. Suspicion spread to the Morse chain of banks, too. The Mercantile, finding its cash being drained away by uneasy depositors, applied to the New York Clearing House for help.[10]

Because of the extreme degree to which the boards of these banks and trusts interlocked, the crisis was virulent. Morse was associated with Charles T. Barney of Knickerbocker Trust Company, who lent him money on occasion. One of the largest in New York, Knickerbocker Trust was targeted by the Clearing House, which demanded resignations. This, coupled with the National Bank of Commerce's refusal to any longer clear their checks, spelled destruction for the trust. On October 21st executives met in a popular restaurant to discuss the emergency. They resolved that only Morgan could save them, and called on him early the following morning.

Morgan the Fixer[edit | edit source]

Morgan had a reputation for fixing these kind of problems. Back in 1893 he had all but single-handedly diffused a similar crisis. In 1890 when the Barings bubble collapsed in Argentina, British capital fled the new world, spurred along by fears that the US government would begin experimenting with bimetallic currency.[11] In 1893, with US gold reserves evaporating, Grover Cleveland approached John Pierpont Morgan Sr. and August Belmont Jr., the American representative of the London Rothschilds.[12] They offered him him $50 million at 3.75%, an outrageous rate which Cleveland declined. But on the night of February 7th Morgan and his coterie arrived at the white house; informed that they could not simply drop in on the President of the United States, Morgan replied “I have come down to see the president, and I am going to stay here until I see him,” and there he waited, playing solitaire through the night.[13] In the morning they were received, and Cleveland told them a public issue of bonds, as opposed to their private scheme, had been decided on. Morgan declared this impossible, and Cleveland asked for his alternative.

Pierpont laid out an audacious scheme. The Morgan and Rothschild houses in New York and London would gather 3.5 million ounces of gold, at least half from Europe, in exchange for about $65 million worth of thirty-year gold bonds. He also promised that gold obtained by the government wouldn’t flow out again. This was the showstopper that mystified the financial world—a promise to rig, temporarily, the gold market .... When the syndicate bonds were offered, on February 20, 1895, they sold out in two hours in London, in only twenty-two minutes in New York.[14]

So in 1907, when the sky was falling on top of New York finance, Morgan seemed the man to call. He formed a team of young bankers loyal to him, including Henry P. Davison of First National Bank and Benjamin Strong of Morgan's own Bankers Trust. He sent these men to audit Knickerbocker's books, and found them wanting. Knickerbocker was allowed to fail October 22.[15]

At this point, even Morgan felt himself out of his depth, and he sought government assistance. Already, back in September, with crisis all but inevitable, Morgan had appealed directly to Theodore Roosevelt. At that time, the Treasury shifted millions of dollars to commercial bank deposits around the nation and tried to limit government withdrawals. Now, October 23, Morgan and other bankers met at a Manhattan hotel with Treasury Secretary George B. Cortel, and the following day Cortel put $25 million in government funds at Pierpont’s disposal.[15] Through the rest of October and into November Morgan affected a series of last minute miracles, saving the New York Stock Exchange, a number of trusts, and New York City itself. By November, the Treasury was again intervening, issuing "$150 million in low-interest bonds and certificates and permitted the banks to use the government securities as collateral for creating new currency — an expedient device for pumping up the money supply in a hurry."[16] Effectively, the alliance between Morgan and the US treasury was attempting to act as a central bank by providing emergency liquidity.

In all, the devastation was palpable. New York's trusts had lost 48% of their deposits.[17] 68 The stock market plunged 40% and steel production was severely reduced.[18] In the wake of such a crisis it was readily apparent that something had to be done. A decade before, Morgan and his syndicate had defused the 1893 Crisis with relative ease, but in 1907 Morgan needed the backing of the US treasury and even then it was a close thing. The age of paternalistic Morgan bailouts had come to an end, and Morgan himself was growing old. After the panic subsided, Senator Nelson W. Aldrich declared, “Something has got to be done. We may not always have Pierpont Morgan with us to meet a banking crisis.”[19]

Jekyll Island and the push for the Federal Reserve[edit | edit source]

To this end, the National Monetary Convention was established by the Aldrich–Vreeland Act of May 8, 1908. Chaired by Nelson Aldrich, the republican whip and most powerful senator at that time, the work was mainly carried on by him and economist A. Piatt Andrew, assistant to the commission.[20] They were to tour Europe, studying central banking practices there, and report back with a plan of banking reform for the United States. Morgan was intimately involved. During the leadup to the commission's departure, he received a coded cable saying that Henry P. Davison would advise Aldrich: “It is understood that Davison is to represent our views and will be particularly close to Senator Aldrich.”[21] And before the commission left for Europe, Davison went ahead to England in order to meet with Morgan, who requested a private central bank akin to the English model.[21]

Having grasped it, they brought it home. The National Monetary Commission returned from Europe fall 1908, and the product of their work, 23 volumes of studies and interviews, began to appear fall 1910. And November of that year, a secret meeting attended by representatives of the great financial houses was hammering out in substance the function and structure of the Federal Reserve. Already with the National Monetary Convention, men like Aldrich were aware of the hay muckrakers could make with the frank reality that a small circle of political and financial elites were planning to unilaterally remake the US banking. Aldrich had written privately, on forming the Convention that "My idea is, of course, that everything shall be done in the most quiet manner possible, and without any public announcement."[22]

But this meeting was on another level of secrecy. Secretaries and wives were told that their bosses and husbands were off for 'duck hunting.' Full names were not used. At close to ten on a cold November night, the last few passengers boarded the last southbound train departing from a nondescript New Jersey rail station. As they began to pull out of the station, a the train shuddered to a stop and began to reverse, pulling back into the station. A moment of confusion was settled by a sudden lurch and the slam of couplers - a car had been connected to the back. But what car? When the passengers arrived at their destination, it was gone.[23]

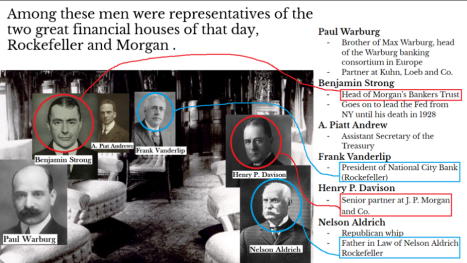

It would be years before anyone knew who boarded that train car that night, or what their destination and purpose were. The car belonged to Nelson Aldrich, and its passengers were a veritable who's who of high-power finance. Nelson himself was a business associate of Morgan and the father in law of Nelson Rockefeller, future vice-president of the United States. He was also a political kingpin, the Republican whip from Rhode Island of whom Theodore Roosevelt confessed "Sure I bow to Aldrich. . . . I’m just a president, and he has seen lots of presidents.”[24] Representing the Morgan camp were Benjamin Strong, head of Morgan's Bankers Trust, and Henry P. Davison, senior partner at J. P. Morgan and Co. and Morgan's right hand during the 1907 Crisis. Under the banner of Rockefeller was Frank Vanderlip, president of National City Bank of New York. Paul Warburg, partner at Kuhn, Loeb & Co., represented that considerable interest, and in some capacity the Rothschilds - not to mention the Warburg consortium itself, headed by his brother Max back in Germany. With his intimate knowledge of continental banking practices, Warburg also provided most of the technical expertise. Finally there was A. Piatt Andrew, the Harvard economist who assisted Aldrich on his tour of Europe, was Assistant Secretary of the Treasury at that time - representing (perhaps) a public interest. Their destination was Jekyll Island, a remote hunting lodge in Georgia. Since 1886 the Island was owned by the Jekyll Island Club, numbered among them J.P. Morgan, Joseph Pulitzer, William K. Vanderbilt, and William Rockefeller.[25] It is here that the Federal Reserve is designed in substance.

If this meeting seems like ancient history: as of 2018, the two largest owners of the New York Fed were Citibank (formerly National City Bank of New York) with 42.8% and JPMorgan Chase (formerly JP Morgan and Co.) with 29.5% of shares.[1] Both of these firms had representatives on Jekyll Island, and moreover the financial houses they represent, Rockefeller and Morgan respectively, were the prime movers of creating the Federal Reserve.

The Public Relations Campaign[edit | edit source]

There was only one problem: the utter lack of enthusiasm for their proposals outside of a narrow circle of bankers. In Warburg's opinion, "it was certain beyond doubt, that unless public opinion could be educated and mobilized, any sound banking reform plan was doomed to fail."[5]

To this end, the bankers formed and financed the National Citizens' League for the Promotion of Sound Banking, a nationwide public relations organization, intended [according to Warburg] to "carry on an active campaign of education and propaganda for monetary reform, on the principles ... outlined in Senator Aldrich's plan." Although the league appeared to spring from grass roots in 1911, it was from the outset "practically a bankers' affair." Great pains were taken to keep New York's role in the league hidden, given prevailing populist prejudice against Wall Street. Warburg recognized that "it would have been fatal to launch such an enterprise from New York; in order for it to succeed it would have to originate in the West."[5]

With this purpose in mind, the organization was funded by the various clearinghouses. Quotas were assigned: $300,000 to the New York Clearing House, $100,000 to that of Chicago, and the rest of the estimated $500,000 price tag to various others.20 The league published 15,000 copies of "Banking Reform," a book on currency reform. A fortnightly journal of the same name with a circulation of 25,000 was also established. They published 950,000 pamphlets of pro-Aldrich Plan statements and speeches, and flooded newspapers across the country with "literally millions of columns" of copy.[5]

Passage[edit | edit source]

In 1912 Aldrich the republican kingpin brought the bill, but was defeated; however, the bill was then repackaged and brought forward by Carter Glass of the democratic party. By the end of Autumn, 1913 everything was falling into place. In October, the National Citizens League's executive committee shut down, satisfied "that the work of the organization has been practically completed and success has been achieved."[26] On December 19th, the Senate passed the bill and it reached the desk of Woodrow Wilson December 23, 1913. He insisted on one change, a Federal Reserve Board in Washington, and signed the bill.[27]

Early Years[edit | edit source]

With the advent of elastic currency, capitalist crises could be forestalled. As Forgan, a banker and key agitator within the American Bankers Association would write, looking backward from 1922, "It is a well known fact that the banks have been and are carrying many industries which would have been forced to the wall, injuring our whole credit structure, had it not been for the fact that the banks in turn have been able to obtain needed currency from the Federal Reserve Banks by rediscounting notes."[28] On top of this, he writes, it "is difficult to see how we could have weathered the storm of the War."[28]

Structure and Powers[edit | edit source]

The New York Fed[edit | edit source]

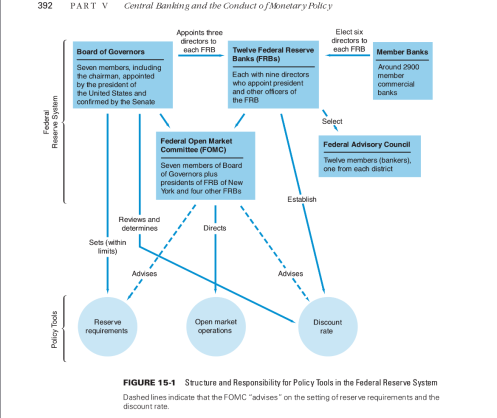

Real power in the system resides with the New York Fed, which conducts Open Market Operations, implements monetary policy, and deals with all international relations. Over time this concentration of influence has diffused, but only slightly.

At the first board meeting, Benjamin Strong, a Morgan man and Jekyll Island attendee, was elected governor. He would spend the next fourteen years working tirelessly alongside Montagu Norman, Governor of the Bank of England from 1920 to 1944, to reinstate an international gold standard. Norman - like the Morgans - was a Nazi collaborator and member of the Anglo-german fellowship. He funded the rearmament of Germany with loans, transferred gold from Czech to Nazi bank accounts,[29] and was a close personal friend of nazi central bank leader, Hjalmar Schact.[30]

During the 1970s Petrodollar Recycling was largely handled through the New York Fed, with 30 percent of Saudi Arabia's total portfolio (70% of their US assets) held in a New York Fed account in 1978.[31] This upset Arthur Burns, Chairman of the Board of Governors, who saw this as an attempt by the New York Fed to reassert dominance.[32]

Monetary Operations[edit | edit source]

The Federal reserve handles money supply through four main levers, all aimed at increasing or decreasing the federal funds rate, which is the rate at which banks make overnight loans to each other. This is what is referred to when it is said that the fed is 'changing interest rates.' These operations aim either to effect supply or demand.[33]

Open Market Operations (Supply)[edit | edit source]

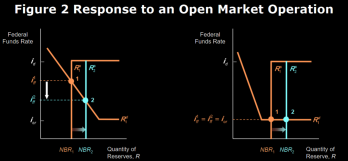

First, and used more commonly than any other method since the 1980s, are Open Market Operations conducted by the New York Fed under the oversight of the Federal Open Market Committee. Primary dealers keep in contact through a dedicated desk at the NY Fed, and buy Governmental bonds from the fed using TRAPS (Trading Room Automated Processing System), a software used exclusively for these transactions. There are two types, defensive and dynamic. Defensive operations try to stabilize the market in response to some externality. For this reason, they are usually temporary measures like repo or matched sale-purchase agreements. Repo is when the fed buys securities with an understanding that they will be returned at a future data, and matched sale-purchase agreements are just the opposite, the Fed selling with an agreement for future re-acquisition. Dynamic operations, like that of Jerome Powel in March of 2023 to raise interest rates, are when the fed wants to make a change in the market, in this instance to fight inflation.

For an example of how this money creation might work, imagine a transaction between the Fed and Wells Fargo. Say the economy is slowing down and the Fed wants to gas it up, they might purchase 100 government securities from Wells Fargo. Wells Fargo will have less government securities (issued at the discretion of the Treasury), and Fed will have more. Under the federal reserve system, minimum reserves are set, and Banks are required to keep these required reserves (RR) in an account at the Fed. So in return for the government issued securities, the Fed credits the account the Bank has with them. Just writes something on a line. This increases the Banks reserves, increasing the amount they can lend. In economese this increases the Monetary Base (and, necessarily, the Money Supply) by 100. If the bank chooses to keep it in currency rather than deposits, then reserves stay the same but the effect on the monetary base is the same. In the case of sales it is just the opposite and the money supply decreases.

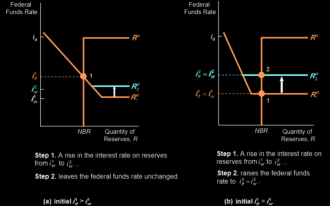

In the chart, purchases increase the amount of non-borrowed reserves, shifting the vertical portion of the supply curve right and thereby lowering the federal funds rate, leading to an increase in overall market liquidity. In the second, because the federal funds rate cannot fall below the interest rate paid on reserves, we hit the flat section and there is no effect on federal funds rate

Discount Rate (Supply)[edit | edit source]

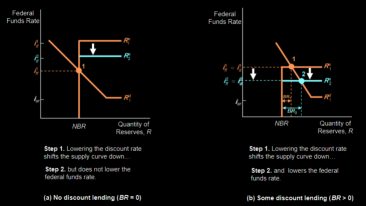

A second supply targeting method is to charge the discount rate. Banks can borrow from each other or from the Fed. If they borrow from each other they they face the federal funds rate. If they borrow from the Fed they face the discount rate. Since 2003, Reserve Banks establish the primary credit rate at least every 14 days, subject to review and determination of the Board of Governors.

Federal Reserve Banks have three main lending programs for depository institutions — primary credit, secondary credit and seasonal credit. Primary credit is offered on a very short-term basis as a backup rather than a regular source of funding, and borrowers are not required to seek alternative sources of funds before requesting. Secondary credit is also short term and is offered to banks not eligible for primary credit. It is meant to get people back to normal market funding. Seasonal credit is available to relatively small depository institutions to meet regular seasonal funding needs.

As we can see, the discount rate is represented by the horizontal portion of the supply curve, and changes here will only have an effect if the market is in a state where the discount window rate is desirable. If this is the case, then lowering the discount rate lowers the federal funds rate and vice versa.

Requirement Ratio (Demand)[edit | edit source]

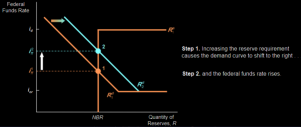

Open Market Operations and the Discount Rate effect supply, but the Federal Reserve has two more methods, each effecting demand. First, they can change the requirement ratio, which is the amount of reserves banks are required to keep in the with the fed. Because these reserves cannot be used for investment, increasing the required reserves increases demand, shifts demand for funds right, lowering the federal funds rate (increasing liquidity), or vice-versa.

Interest on Reserves (Demand)[edit | edit source]

Another way to affect demand is by changing interest on reserves. Until 2008, the Federal Reserve did not pay interest on reserves banks held with them. First authorized by Congress 2006 with implementation scheduled for 2011, the program was fast tracked in response to the crisis. This was pursuant of Fed policy: buying up toxic assets while minimizing the effect this would traditionally have had on general liquidity. Fed officials feared the federal funds rate would dip below their target and cause price instability.

To avoid this outcome, the Fed "sterilized" the effect of liquidity injections on the overall economy: It sold an equal amount in Treasury securities from its own account to banks. Sterilization offset the injections' effect on the monetary base and therefore the overall supply of credit, keeping the total supply of reserves largely unchanged and the fed funds rate at its target. Sterilization reduced the amount in Treasury securities that the Fed held on its balance sheet by roughly 40 percent in a year's time, from over $790 billion in July 2007 to just under $480 billion by June 2008. However, following the failure of Lehman Brothers and the rescue of American International Group in September 2008, credit market dislocations intensified and lending through the Fed's new lending facilities ballooned. The Fed no longer held enough Treasury securities to sterilize the lending.

This led the Fed to request authority to accelerate implementation of the IOR policy that had been approved in 2006. Once banks began earning interest on the excess reserves they held, they would be more willing to hold on to excess reserves instead of attempting to purge them from their balance sheets via loans made in the fed funds market, which would drive the fed funds rate below the Fed's target for that rate. When the Fed stopped sterilizing its liquidity injections, the monetary base (which is comprised of total reserves in the banking system plus currency in circulation) ballooned in line with Fed lending, from about $847 billion in August 2008 to almost $2 trillion by October 2009. However, this did not result in a proportional increase in the overall money supply (Figure 1). This result is likely due largely to an undesirable lending environment: Banks likely found it more desirable to hold excess reserves in their accounts at the Fed, earning the IOR rate with zero risk, given that there were few attractive lending opportunities. That the liquidity injections did not result in a proportional increase in the money supply may also be due to banks' increased demand to hold liquid reserves (as opposed to individually lending those excess reserves out) in the wake of the financial crisis[34]

In the graph, IOR allows the Fed to place a floor on the federal funds rate (the horizontal line in the supply curve), because banks have little reason to lend at rates below the rate of interest they receive on their reserve balances. The rate is determined by the Board of Governors.

Extraordinary Measures (2008)[edit | edit source]

Above are the conventional methods of monetary policy. In some circumstances, they become insufficient. In particular, there is what is known as the Zero-Lower Bound Problem. Interest rates, for obvious reasons, cannot (usually) be negative, so as they approach zero there comes a point where nothing further can be done. If the economy is still unresponsive, the Fed can, as it did in 2008, take extraordinary measures. One method was to extend the term of discount loans, giving banks longer to pay them back. Another was the Term Auction Facility, through which the Fed extended 3.8 trillion in collateralized loans at rates below the discount rate. The auctions were administered by the New York Fed though loans were offered through all twelve of the Federal Reserve Banks. At the same time, the Fed also began to make large scale purchases of toxic assets.

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/2bsx0wq4jdzo82fk8nhfk/culture/conspiracy-theorists-ask-who-owns-the-new-york-fed-heres-the-answer#:~:text=The%20big%20reveal%20for%20year,29.5%20percent%20of%20the%20total.

- ↑ Marx, Capital V1, Chapter Three: Money, Or the Circulation of Commodities

- ↑ Congressional Record Volume 141, Number 27 (Friday, February 10, 1995) https://web.archive.org/web/20240208025511/https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CREC-1995-02-10/html/CREC-1995-02-10-pt1-PgS2457.htm

- ↑ Gische, David M. “The New York City Banks and the Development of the National Banking System 1860-1870.” The American Journal of Legal History 23, no. 1 (January 1979): 21. https://doi.org/10.2307/844771.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Broz, J. Lawrence. 1999. “Origins of the Federal Reserve System: International Incentives and the Domestic Free-Rider Problem.” International Organization 53 (1): 39–70. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899550805

- ↑ Allen, F.L., G. Morgenson, and M.C. Miller. The Lords of Creation: The History of America’s 1 Percent. Forbidden Bookshelf Series. Open Road Integrated Media, Incorporated, 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=4fwnswEACAAJ. p110

- ↑ Lowenstein, Roger. America’s Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve. New York: Penguin Press, 2015. p 58

- ↑ Lowenstein, Roger. America’s Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve. New York: Penguin Press, 2015. p 59

- ↑ Allen, F.L., G. Morgenson, and M.C. Miller. The Lords of Creation: The History of America’s 1 Percent. Forbidden Bookshelf Series. Open Road Integrated Media, Incorporated, 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=4fwnswEACAAJ. 111

- ↑ Allen, F.L., G. Morgenson, and M.C. Miller. The Lords of Creation: The History of America’s 1 Percent. Forbidden Bookshelf Series. Open Road Integrated Media, Incorporated, 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=4fwnswEACAAJ. p109

- ↑ Chernow, Ron. The House of Morgan, p 105

- ↑ Spence, Richard B. Wall Street and the Russian Revolution: 1905-1925, p42

- ↑ Chernow, The House of Morgan, 109

- ↑ Chernow, The House of Morgan, 110

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Chernow, The House of Morgan. 166-67

- ↑ Greider, William. Secrets of the Temple: How the Federal Reserve Runs the Country. Simon and Schuster, 1989. p278

- ↑ Lowenstein, Roger. America’s Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve. New York: Penguin Press, 2015. 68

- ↑ Lowenstein, Roger. America’s Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve. New York: Penguin Press, 2015. 71

- ↑ Chernow, The House of Morgan, 173

- ↑ Dewald, William G. 1972. “The National Monetary Commission: A Look Back.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 4 (4): 930. https://doi.org/10.2307/1991235.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 Chernow, The House of Morgan, 173

- ↑ Fisher, Keith. 2022. A Pipeline Runs Through It: The Story of Oil from Ancient Times to the First World War. Penguin UK. 389

- ↑ Griffin, The Creature from Jekyll Island, 4-5

- ↑ Lowenstein, Roger. 2015. America’s Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve. New York: Penguin Press. 43

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20220127084144/https://www.jekyllisland.com/history/timeline/

- ↑ Kolko, Gabriel. 1977. The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History, 1900 - 1916. 1. Free Press paperback ed. American History. New York: The Free Press. 245

- ↑ Greider, William. 1989. Secrets of the Temple: How the Federal Reserve Runs the Country. Simon and Schuster. 277

- ↑ Jump up to: 28.0 28.1 Forgan, James B. 1922. “Currency Expansion and Contraction.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 99 (1): 167–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271622209900123.

- ↑ Blaazer, David (2005). "Finance and the End of Appeasement: The Bank of England, the National Government and the Czech Gold". Journal of Contemporary History. 40 (1): 25–39.

- ↑ Forbes, Neil (2000), "Doing Business with the Nazis"

- ↑ David E. Spiro, The hidden hand of American hegemony: petrodollar recycling and international markets, 1999. p113

- ↑ David E. Spiro, The hidden hand of American hegemony: petrodollar recycling and international markets, 1999. p108

- ↑ Mishkin, Frederic S., and Apostolos Serletis. The Economics of Money, Banking and Financial Markets. 4th Canadian ed. Toronto: Pearson Addison Wesley, 2011. (I rely in this section mainly on this work, but intermixed with notes I took in an undergraduate course on Banking; diagrams are from this textbook)

- ↑ The Effect of Interest on Reserves on Monetary Policy, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, 2009https://web.archive.org/web/20231004123632/https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/economic_brief/2009/eb_09-12#:~:text=On%20October%2013%2C%202006%2C%20the,%2C%20to%20October%201%2C%202008.